The health differences between rich and poor people were noticeable even before the COVID-19 pandemic, which has dislocated our lives on two fronts: public health and socioeconomically. International research over the past year has therefore focused intensely on how the crisis is affecting global inequality – in both health and economic terms. This has highlighted the difficult but necessary discussion on the balance between health and wealth to prevent the crisis from increasing inequality even more.

Not everyone is privileged to have a long and healthy life. Inequality in health has been rising in many high-income countries over the past half century. In Denmark, the richest people live about 10 years longer than the poorest people, and this inequality has widened over the past 20 years despite access to a universal healthcare system and generally good public health (1). Healthcare costs are rising as a percentage of GDP, and awareness is increasing of the importance of preventing disease, promoting healthy lifestyles and encouraging good health habits. Nevertheless, the benefits of new and improved health technologies seem to be unequally distributed.

A prevailing hypothesis in economic literature is that people with more education and higher income have more appropriate health behaviour, are better at following health advice and treatments and acquire new technologies more rapidly. This implies that the rapid development of medical innovations intended to benefit everyone tend to favour people with more education. Despite good intentions, medical innovations may therefore contribute to the increasing socioeconomic inequality in health (2).

This socioeconomic inequality in health is the topic of our current research project Behavioural Responses to Health Innovations and the Consequences for Socioeconomic Outcomes conducted at the Department of Economics at the University of Copenhagen.

COVID-19 pandemic has altered health priorities

Rich and poor people differed noticeably in health outcomes long before the COVID-19 pandemic, which has implied a shock to living conditions on two fronts: public health and the economy. Recent international research has therefore studied intensely how the crisis is affecting inequality globally.

The burden of disease and mortality from COVID-19 is unequally distributed across population groups in many countries. Restrictions and the economic disruption have also differentially affected people depending on their occupation, labour market status and education.

The pandemic has emphasized a difficult yet necessary discussion about how to weigh the trade-offs between public health and economic costs. Economic priority-setting has always been required in healthcare, but the COVID-19 pandemic poses new and difficult parameters for setting priorities, including decision-making under great uncertainty and making decisions that have wide-ranging consequences well beyond the healthcare sector.

Efforts to combat COVID-19 have had to be adapted to a wide range of societal considerations involving education for our children and young people, the private sector, transfer payments and tax policy. Human behaviour is yet another significant factor that is difficult to predict – not only how we understand and act in relation to restrictions and contribute to infection control but also how restrictions and behavioural changes affect welfare through such means as mental health and detection of other diseases.

Impaired health

How has the pandemic affected mental health? We investigated this in May and June 2020 during the first lockdown in Denmark. We sent a questionnaire to about 7,800 people 18–75 years old who had also responded to a health survey in 2019. The survey indicated that mental health measured by the Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5) had significantly declined across educational groups in the past year, but especially among women. Analysis of the effects of pandemic-induced changes in work patterns based on data from the United Kingdom (3) indicate that especially women with young children had difficulty in working from home during the lockdown, which worsened their work–life balance.

During and after the lockdown in 2020, the healthcare sector experienced sharp reductions in consultations with general practitioners, hospitalization, outpatient visits and surgery (according to data from the Danish Health Data Authority). Thus, consultations about diseases other than those related to COVID-19 have dropped drastically. This may result from the fear of social contact based on the risk of infection but may also reflect people focusing away from other potential disorders that may later prove to be serious. A study published in BMJ Open (4) revealed that cancelled appointments during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020 helped to magnify pre-existing inequalities in the United Kingdom, primarily among women, ethnic minorities and people with chronic diseases.

Vaccines for all?

Outstandingly effective and successful research and innovation initiatives in several countries and research communities have developed vaccines against COVID-19 in a historically short time. We can thus envision a path out of lockdown that is supported by intensive rollout of vaccination programmes around the world. The current uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine is generally high in Denmark. According to Statens Serum Institut (5), 89% of the delivered doses of COVID-19 vaccine were given and registered in Denmark’s administrative regions (as of 12 April 2021).

However, the level of vaccine uptake is not as high in other European countries. And within the past 20 years or so, anti-vaccination campaigns, also in Denmark, have created doubts about the safety and efficiency of major vaccination programmes, which in some places has resulted in vaccine coverage levels insufficient to guarantee herd immunity.

So who prefers to get the jab? Figures from the HOPE (How Democracies Cope with COVID-19) Project at Aarhus University show that, in mid-January 2021, 87% of the population of Denmark either fully or partly agreed that they wanted to be vaccinated against COVID-19. These figures are in accordance with the results from the survey we conducted during the first lockdown in Denmark between May and June 2020.

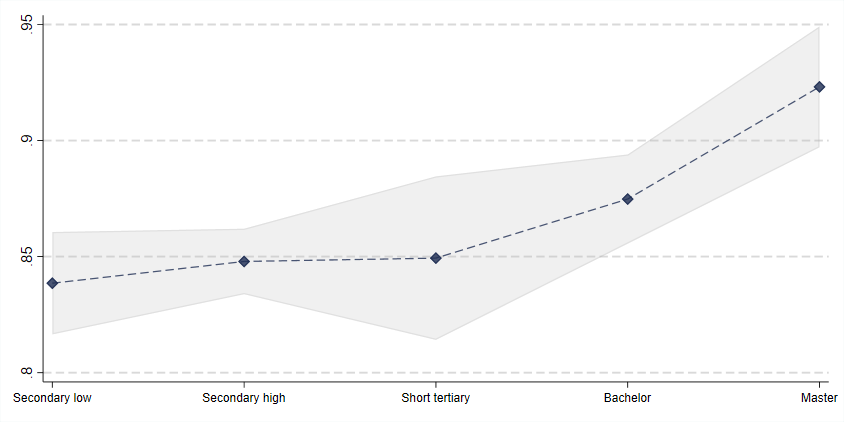

About 86% of the respondents answered that they would definitely or almost definitely agree to be vaccinated against COVID-19 if it became available. In our study, we also found that the desire to be vaccinated is associated with educational attainment. Thus, the desire to be vaccinated was almost 10 percentage points higher for people with a long tertiary education than people with only lower-secondary education. The desire to be vaccinated is roughly the same among men and women after adjusting for education level.

We also asked the respondents to rate on a scale from 1 to 10 the extent to which they agreed with the statement that vaccines are important in combating diseases and with the statement that the side-effects of vaccines are often more serious than the disease itself. We found that people with more education were significantly more likely to believe that vaccines are important, and people with less education agreed significantly more that side-effects are often more serious than the disease itself.

Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination in Denmark, May–June 2020

Source: Own survey data carried out in May–June 2020 among around 7,800 randomly selected Danes aged 18–75 years. The question asked was “If a vaccine against the coronavirus is found, will you then get vaccinated?” Answers are counted as positive if people responded “Yes, as soon as possible” or “Yes, eventually”.

Vaccine scepticism is contagious

In Denmark, the uptake of vaccines has historically been high, but there have been periods of great vaccine scepticism, especially in the past 20 years. A now retracted article in The Lancet reported on cases of autism among young children that occurred after MMR vaccination, and Danish media have run stories about young girls who experienced fatigue and indefinable pain following HPV vaccination. Such reports fuel vaccine scepticism, and the lack of uptake of the MMR vaccination has contributed to the foundation for measles outbreaks in several European countries.

Vaccine scepticism is not isolated to individual vaccines. A research article published in Vaccine (6) shows that there are contagious effects across vaccination programmes. In Denmark, negative media coverage of the HPV vaccine in 2013 and 2015 meant not just a reduction in HPV vaccination among young girls but also fewer MMR vaccinations among the same group.

The emergence of a suspicion that some COVID-19 vaccines may be associated with an increased risk of blood clots means that both investigating possible side-effects and disseminating this knowledge to the public in a nuanced and convincing way will be essential. These considerations should also lead to a broad and thorough discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of vaccines as an effective tool for mitigating the effects of recurring epidemics.

Although it is still too early to assess how COVID-19 is affecting inequality overall, recent research suggests that the pandemic has reduced awareness of other diseases and mental health and that the effects may vary across socioeconomic groups and between the sexes. Further, a possible increase in vaccine scepticism may contribute to further inequality in health. Experience from previous periods of widespread vaccine scepticism in connection with the HPV vaccine indicates that the public health authorities must give high priority to a broad-based public information initiative.